Rotimi Fani-Kayode: Tranquility of Communion

Hushed as a ritual, sensual and disarmingly tender, Fani Kayode’s work builds bridges.

A review by Mackenzie Perras. Tranquility of Communion runs until May 25th at Polygon Gallery, 101 Carrie Cates Court in North Vancouver.

If you’re heading into the main galleries at Polygon in the next few weeks—and I’d strongly recommend you do—you’ll come around the corner and be faced with a gorgeous man, larger than life and naked, perched on his tiptoes at the top of the staircase studying your ascent. His gaze is obscured, but you really do feel his watchful intensity and silent curiosity probing you as you head up into the exhibit anyways. Like much of Kayode’s work, this untitled 1985 photograph inspires a deep, curious quiet that immediately washes away the bubbling noise of the street and the raucous gift shop below, marking a cryptic transition into a different kind of space: somewhere softer, quieter, and safer.

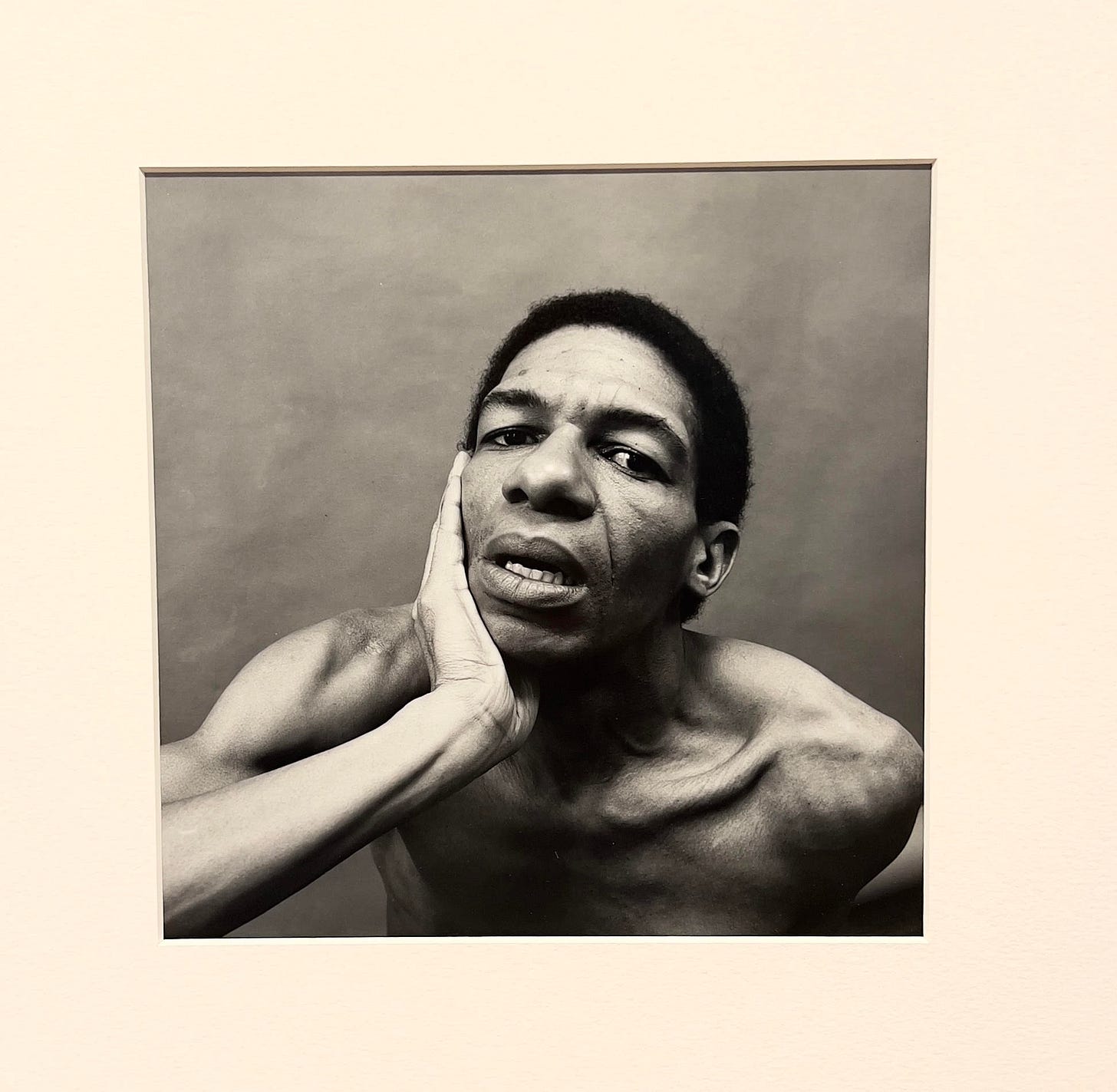

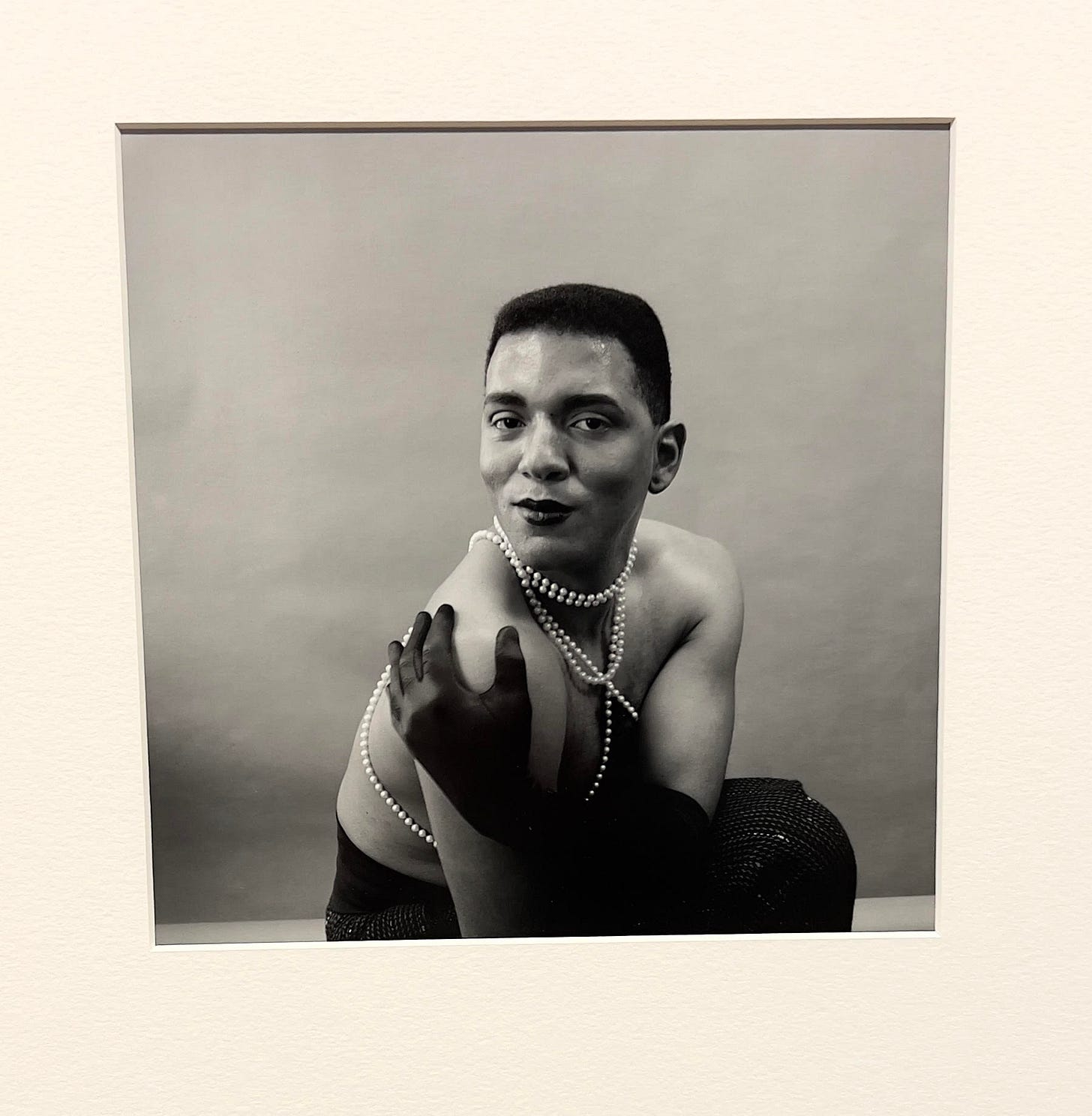

The show is divided into a few sections and opens with The Theatre, a series of large, mythological colour prints. It brings together the last full body of work Kayode made before dying from complications of AIDS—Nothing to Lose: Bodies of Experience—and is a tour de force we are blessed to have brought to Canada. Sculptural, emotionally accessible and fueled by myths and rituals of Yoruba spirituality as much as gay and fetish subcultures, these pictures deftly balance vitality and softness. Gazes play a bouncing game, as fruit, dirt, and the jagged shells of sea creatures are consumed; fetish gear and Esu masks enable models to transform and access supernatural qualities while crowns and coffins of flowers lend something heartbreakingly elegiac to the artist’s goodbye. Shot in 1989 and produced alongside his longtime romantic partner and collaborator Alex Hirst, the brown studio backgrounds, intensely controlled lighting and highly staged setups give these pictures an otherworldly magnetism that feels like an African Midsummer Night’s Dream emblazoned with the Yoruba faith’s Orishas and their potent powers over the forces of nature.

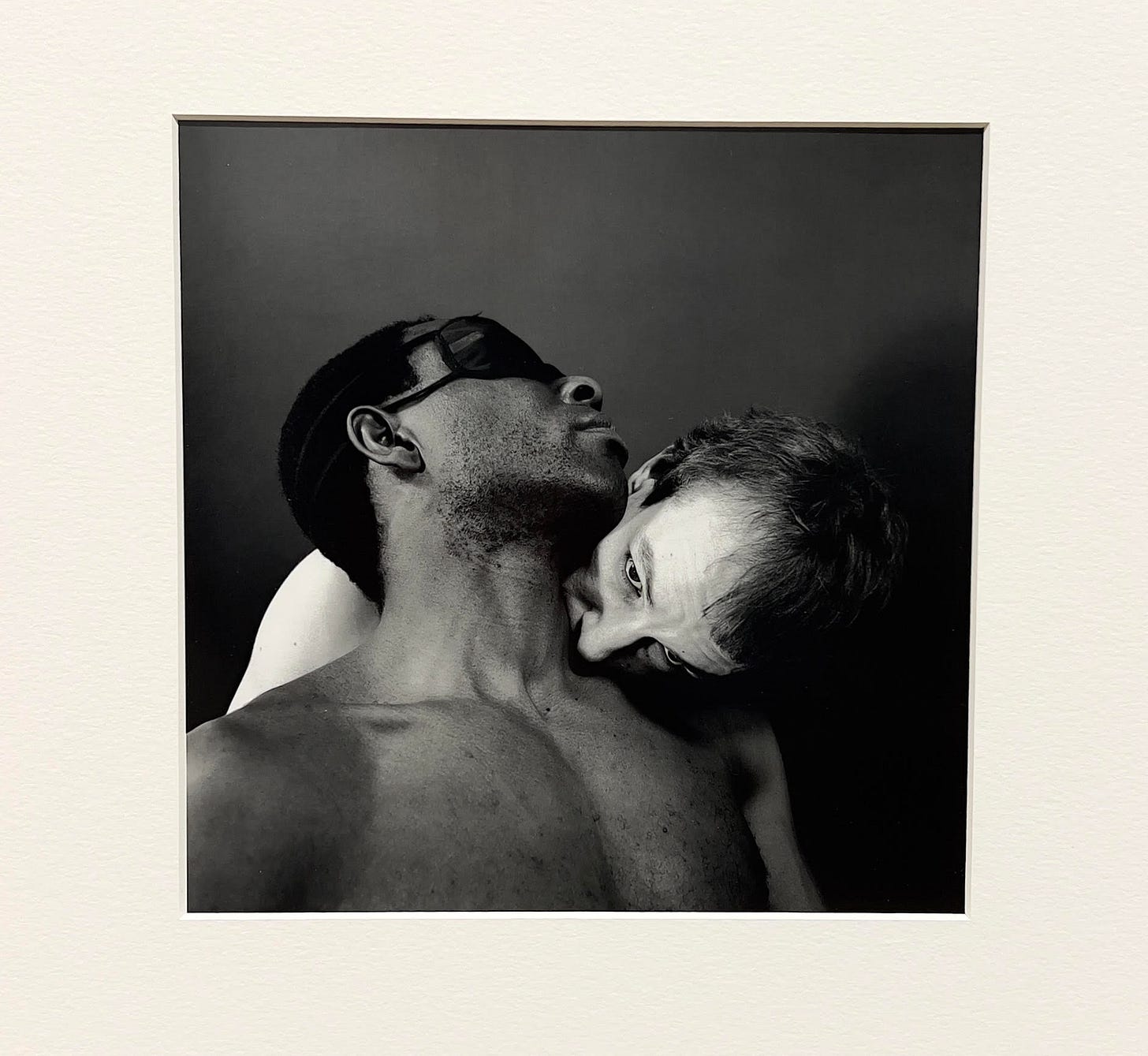

The Archive is filled with much undated, untitled student-era work of the artist and early punk polaroids, all of it fun to look at—the viewpoint was already rock solid. But don’t miss the late, 1989 gum bichromate prints either: these unassuming, painterly photographs exist outside mechanical reproduction and are quite useful for understanding how Kayode thought of a photo as a magical membrane, a living surface onto which viewers were reflected and through which they could heal, grow, and reimagine themselves in novel ways. Moving into The Museum, an assembly of black and white silver gelatin prints and the largest collection of Kayode’s work in the show, feels like entering the artist’s bedroom while he’s just dozed off with a couple friends. I noticed myself speaking in a hushed tone—others in the gallery, too—almost like we were hesitant to wake them or disturb the subjects of the photographs in the privacy of their intimate moments. Tranquility of Communion wraps up with The Studio, a reading nook decked out with wall-sized copies of some crop-marked contact sheets and a tv screening the British Film Institute’s Rage and Desire, which is definitely worth sticking around for.

The context in which these images were created was one at first glance quite different from today: at the height of the AIDS epidemic, when visible homosexuality and interracial coupling were highly stigmatized and villainized. Any shock value these images may have had, however, has long since worn off—revealing disarmingly tender and sensitive pictures, suffused with a powerfully humanizing compassion and a keen sense of humour. The language is familiar, but the syntax is completely queer: Orpheus and his lyre, Magritte’s bowler hat and pipe and myriad other dreamlike, familiar symbols are tweaked or twisted to let us know we’re in Kayode’s private world, now. This place, I imagine, is as much a bedroom as a studio. It externalizes a politics of care and encourages a sense of shared humanity, choosing to highlight the erotic nuance and personal idiosyncrasy his community was so often forced to hold back in public. Kayode’s work builds bridges to many people who had previously felt separate or distinct from his milieu, stoking a blazing compassion not unlike what the best religious art does.

Born in Nigeria in 1955, Kayode often thought of himself as a triple outsider: he was black in a world built for the white; he was gay in a time when homosexuality was feared as a kiss of death; and he abandoned the upper-class expectations of his parents to work at the cultural fringe of subculture and art. After spending a couple hours in the delicate space of his pictures, however, I think Kayode was above all things a powerful humanizer. While circumstance may have cut his life brutally short—he passed away at just 34, followed three years later by his partner Alex Hirst—I have the suspicion time has been much kinder to Rotimi Fani-Kayode than circumstance ever was. Thirty-five years time has stripped these images of their scandal to reveal them gloriously naked and unabashed, glowing with power and potent magic and silky-soft in their quiet, compelling empathy. We see his cast of characters not as categories—drag queen, black stud, gay couple—but as complex and deeply human subjects worthy of conversation and getting to know. Kayode’s great victory, and maybe the most radical part of his practice, is inoculating us against the easy hate of a categorical understanding of humanity. Viewing this work has the potential to generate emotional antibodies—still so urgently necessary in today’s careening, digitized world—against the illness of ignorant hate. Like I said, it’s a medicine I’d highly recommend a dose of.

A view up the staircase towards the main Polygon galleries, with Untitled, 1985.

Detail from Nothing to Lose (Bodies of Experience) IV, 1989.

Detail from Nothing to Lose (Bodies of Experience) X, 1989.

Detail from Untitled (Bodies of Experience), 1989.

Nothing to Lose (Bodies of Experience) IX, 1989.

Three one-of-a-kind gum bichromate prints, all titled Untitled (Cargo of the Middle Passage), 1989.

City Gent, 1988.

Untitled, 1988.

Untitled, 1988.

Untitled, 1988.

Love your writing Mackenzie. Can’t wait to see this now!